A bit of history

A shared pointer was introduced in 1999 as part of the Boost Library Collection. It existed even before Boost had version numbers. The only alternative the standard C++ library could provide was auto_ptr. Auto pointer became famous mainly for its disadvantages, and as a result, it was rarely used. Finally, the auto pointer was deprecated in C++ 11 and completely removed in C++ 17. In C++ 11, boost::shared_ptr finally made it to the standard library together with other smart pointers. For over a decade, Boost’s shared pointer was the most used smart pointer in C++.

A few words about how shared_ptr works

From a very simplified point of view, a shared pointer has two pointers: one to an object at the heap and another to a reference counter of shared instances.

- Every time a shared pointer’s copy-constructor is called, the shared pointer increments the counter

- Every time a shared pointer’s assignment operator is called, the right-hand pointer increments its counter, and the left-hand pointer decrements

- Every time a shared pointer’s destructor is called, it decrements its counter

- If the counter equals zero, the object is deleted

The ideal usage

With the shared pointer, a programmer can create a variable at the heap and pass it wherever they want without caring about memory deallocation because, at some point, it happens automatically. It is fantastic, isn’t it? Let us see!

Reference counter and multi-threading

Shared pointers are often used in multi-threaded programs, where several pointers may update the same reference counter from different threads. The counter is implemented as an atomic, if hardware allows, or with a mutex to prevent data races. The update of atomic variables is more expensive than regular primitives. In order to see the influence of atomic counter updates on performance, I have prepared a code snippet that passes a shared pointer by value and by reference one million times.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

#include <memory>

using namespace std::chrono;

using shared_ptr_t=std::shared_ptr<int>;

void shared_ptr_receiver_by_value(shared_ptr_t ptr) {

(void)*ptr;

}

void shared_ptr_receiver_by_ref(const shared_ptr_t& ptr) {

(void)*ptr;

}

void test_copy_by_value(uint64_t n) {

auto ptr = std::make_shared<int>(100);

for(uint64_t i = 0u; i < n; ++i) {

shared_ptr_receiver_by_value(ptr);

}

}

void test_copy_by_ref(uint64_t n) {

auto ptr = std::make_shared<int>(100);

for(uint64_t i = 0u; i < n; ++i) {

shared_ptr_receiver_by_ref(ptr);

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

uint64_t n = (argc == 3 ) ? std::stoull(argv[2]) : 100;

auto t1 = high_resolution_clock::now();

if(atoi(argv[1]) == 1) {

test_copy_by_value(n);

} else {

test_copy_by_ref(n);

}

auto t2 = high_resolution_clock::now();

auto time_span = duration_cast<duration<int64_t, std::micro>>(t2 - t1);

std::cout << "It took me " << time_span.count() << " microseconds.\n";

return 0;

}

The difference is quite significant:

$ ./cpu_atomic_copy.bin 1 999999

It took me 3616 microseconds.

$ ./cpu_atomic_copy.bin 2 999999

It took me 2 microseconds.

If shared pointers are often passed to functions, it is preferred to give them by references unless a function executes in a separate thread.

Memory allocation

This is the initialization of std::shared_ptr I usually see:

1

2

// let us assume that new int(42) does not throw

auto ptr = std::shared_ptr<int>(new int(42));

What happens in the code?

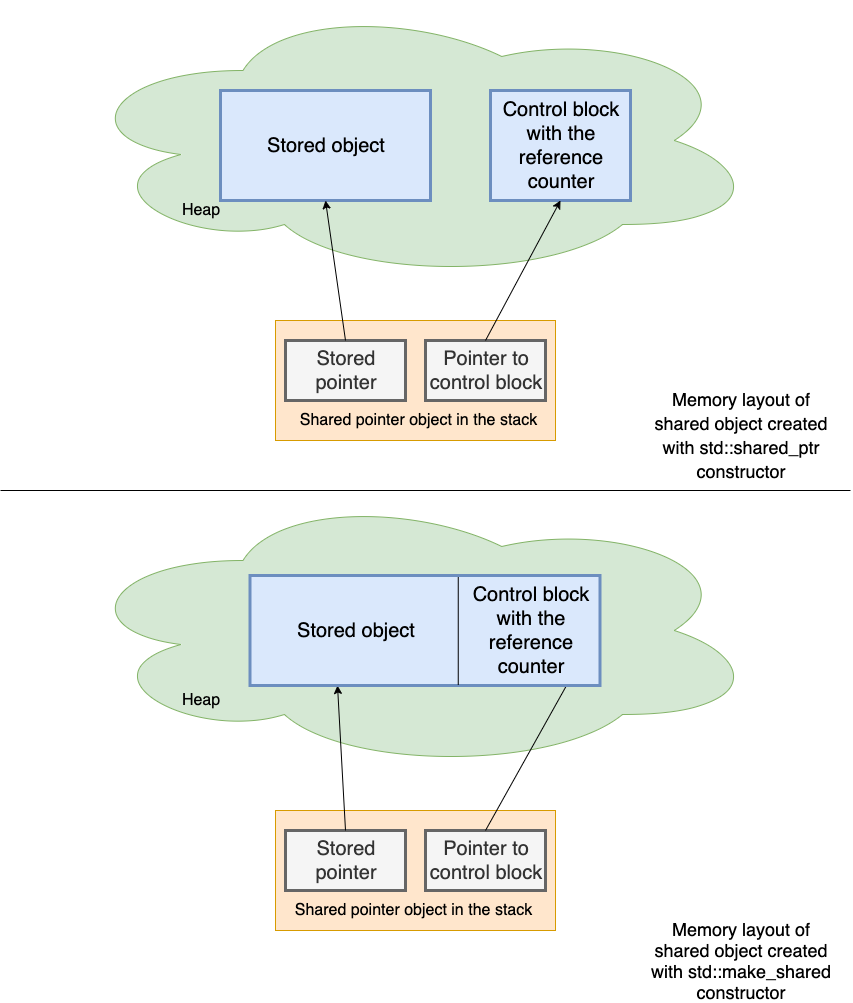

- The operator

newallocates memory at the heap for the integer “42”, and the shared pointer’s constructor saves the pointer to this memory in the stored pointer - The shared pointer’s constructor allocates memory at the heap for the control block with the reference counter and saves it as another internal pointer

Why is it bad?

- The code does two memory allocations at the heap for a single object

- The shared pointer’s data is located in separate parts of the heap. Which potentially may lead to a higher cache miss rate.

How to fix it? std::make_shared comes to help:

1

auto ptr = std::make_shared<int>(42);

It looks almost the same, but make_shared makes only one allocation of a contiguous piece of memory used for storing both the stored object and the control block with the reference counter. Afterward, make_shared calls in place constructor for the stored object and control block.

The picture below shows the difference in the memory layout of shared pointers created in two ways.

I prepared the following code that creates shared pointers in a loop using a constructor and make_shared.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

#include <iostream>

#include <memory>

#include <vector>

void test_shared_ptr(size_t n) {

std::cout << __FUNCTION__ << "\n";

std::vector<std::shared_ptr<size_t>> v;

v.reserve(n);

for(size_t i = 0u; i < n; ++i) {

v.push_back(std::shared_ptr<size_t>(new size_t(i)));

}

}

void test_make_shared(size_t n) {

std::cout << __FUNCTION__ << "\n";

std::vector<std::shared_ptr<size_t>> v;

v.reserve(n);

for(size_t i = 0u; i < n; ++i) {

v.push_back(std::make_shared<size_t>(i));

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

size_t n = (argc == 3 ) ? atoi(argv[2]) : 100;

if(atoi(argv[1]) == 1) {

test_shared_ptr(n);

} else {

test_make_shared(n);

}

return 0;

}

To visualize the results, I run it inside Valgrind’s “memcheck”.

$valgrind --tool=memcheck ./memory_allocation.bin 1 100000

==3005== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==3005== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==3005== Using Valgrind-3.13.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==3005== Command: ./memory_allocation.bin 1 100000

==3005==

test_shared_ptr

==3005==

==3005== HEAP SUMMARY:

==3005== in use at exit: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==3005== total heap usage: 200,003 allocs, 200,003 frees, 4,873,728 bytes allocated

==3005==

==3005== All heap blocks were freed -- no leaks are possible

==3005==

==3005== For counts of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -v

==3005== ERROR SUMMARY: 0 errors from 0 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)

$valgrind --tool=memcheck ./memory_allocation.bin 2 100000

==3010== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==3010== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==3010== Using Valgrind-3.13.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==3010== Command: ./memory_allocation.bin 2 100000

==3010==

test_make_shared

==3010==

==3010== HEAP SUMMARY:

==3010== in use at exit: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==3010== total heap usage: <100,003 allocs, 100,003 frees, 4,073,728 bytes allocated

==3010==

==3010== All heap blocks were freed -- no leaks are possible

==3010==

==3010== For counts of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -v

==3010== ERROR SUMMARY: 0 errors from 0 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)

The output shows 200,003 allocations when using the constructor versus 100,003 with std::make_shared.

I would recommend giving preference to make_shared over creating via the constructor, except for the cases that will be covered later in this post.

For more information std::make_shared, refer to cppreference.com.

Reference cycles

The following piece of code is a simplified example of a reference cycle. There is an instance of struct A that owns an instance of struct B when the instance of B owns the instance of A.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

#include <iostream>

#include <memory>

struct B;

struct A {

~A() { std::cout << "dtor ~A\n"; }

std::shared_ptr<B> b;

};

struct B {

~B() { std::cout << "dtor ~B\n"; }

std::shared_ptr<A> a;

};

void test() {

auto ptrA = std::make_shared<A>();

auto ptrB = std::make_shared<B>();

ptrA->b = ptrB;

ptrB->a = ptrA;

}

int main() {

test();

return 0;

}

Ideally, after the flow exits the function test, the destructors of A and B would print their messages. However, the following output shows the opposite: the destructors are never called.

$ ./reference_cycle.bin

$

As mentioned above, the example is simple, and a seasoned developer can break the cycle by introducing a third class. However, reference cycles can contain a long chain of objects, making identifying them harder.

When adding another type is not an option, the standard class has weak_ptr.

A weak pointer does not own the object at the heap but only points to a shared pointer (the shared pointer’s counter equals 1). To use the object via a weak pointer, a user has to call the lock method that creates an additional instance of the shared pointer. Thus, the caller becomes a co-owner of the object at the heap.

In the code snippet below, B’s shared pointer to A is replaced with weak_ptr.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

struct B;

struct A_ {

~A_() { std::cout << "dtor ~A\n"; }

std::shared_ptr<B> b;

};

struct B {

~B() { std::cout << "dtor ~B\n"; }

// one of the pointers becomes weak

std::weak_ptr<A> a;

};

void test_() {

auto ptrA = std::make_shared<A>();

std::cout << "A address: " << ptrA.get() << std::endl;

auto ptrB = std::make_shared<B>();

ptrA->b = ptrB;

ptrB->a = ptrA;

std::cout << "Number of references to A: "

<< ptrB->a.use_count()

<< std::endl

<< "A address: "

<< ptrB->a.lock().get()

<< std::endl;

}

int main() {

test_();

return 0;

}

The output proves that both destructors are run on the exit of the flow.

$ ./reference_cycle.bin

A address: 0x7f83564017d8

Number of references to A: 1

A address: 0x7f83564017d8

dtor ~A

dtor ~B

If no shared pointers are left, and the object is destructed, the weak pointers lock method returns a null shared pointer.

It is essential to check the pointer before using it, and the only thread-safe way to do it is the following:

1

2

3

4

auto new_shared = weak.lock();

if (new_shared) {

new_shared->method();

}

More information about std::weak_ptr, refer to cppreference.com

std::make_shared together with std::weak_ptr

By now, we know that std::make_shared saves memory allocations, and std::weak_ptr can break reference cycles. But what happens when they are used together?

In the next code sample, struct B did not change, but A is slightly different: now, it has an array of characters str. The method create_make_shared_and_return_weak_ptr creates the same initial reference cycle A<=>B and returns a weak and a raw pointer to the A. The routine test_make_shared_with_weak prints if the received weak pointer can acquire a strong pointer and how many pointers are left. Additionally, it prints the content of A::str using the raw pointer.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

struct A {

// Let us add char buffer str to class A

char str[256];

A() {

strcpy(str, "AAAAAAAAA");

}

~A() { std::cout << "dtor ~A\n"; }

std::shared_ptr<B> b;

};

struct B {

~B() { std::cout << "dtor ~B\n"; }

std::weak_ptr<A> a;

};

std::tuple<std::weak_ptr<A>,A*>

create_make_shared_and_return_weak_ptr() {

auto ptrA = std::make_shared<A>();

std::cout << "A address: " << ptrA.get() << std::endl

<< "A::str = " << ptrA->str

<< std::endl;

auto ptrB = std::make_shared<B>();

ptrA->b = ptrB;

ptrB->a = ptrA;

std::cout << "Number of references to A: " << ptrB->a.use_count()

<< std::endl;

return {ptrB->a, ptrB->a.lock().get()};

}

void test_make_shared_with_weak() {

auto[weak, raw_ptr] = create_make_shared_and_return_weak_ptr();

std::cout << "Returned from create_make_shared_and_return_weak_ptr"

<< std::endl;

auto strong = weak.lock();

std::cout << "Number of references to A: "

<< strong.use_count()

<< std::endl;

std::cout << "Stored address: " << strong.get() << std::endl;

std::cout << "Value of A::str stored by original address of A: "

<< raw_ptr

<< " is: " << raw_ptr->str << std::endl;

}

int main() {

test_make_shared_with_weak();

return 0;

}

As a result of executing this test, the destructors of A and B are called, and the returned weak pointer states that there are no shared pointers left (Number of references to A: 0). Only the content of A’s str is still untouched. Some operating systems do not clear the released memory but mark it as free. After I rewrote it with a custom free method that zeroed the memory, the result was the same – the memory was never freed.

$ ./reference_cycle.bin

Aaddress: 0x7fd37ac01918

A::str = AAAAAAAAA

Number of references to A: 1

dtor ~A

dtr ~B

Returned from create_make_shared_and_return_weak_ptr

Number of references to A: 0

Stored address: 0x0

Value of A::str stored by original address of A: 0x7fd37ac01918 is: AAAAAAAAA

Here is the explanation from cppreference.com:

If any std::weak_ptr references the control block created by std::make_shared after the lifetime of all shared owners ended, the memory occupied by T persists until all weak owners get destroyed as well, which may be undesirable if sizeof(T) is large.

As mentioned before, make_shared saves the stored object and reference counter in a single piece of memory. On one hand, the weak pointers need access to the reference counter to track the availability of strong pointers. On the other, it is impossible to free a part of the memory allocated within one malloc call. The only possible solution is to call the object’s destructor explicitly but only to clean the memory once there are no weak pointers left.

Thus, make_shared and weak_ptr do not co-exist well.

Design problems

The most severe problem with shared pointers is not implementation nuances but the need for their usage. A shared pointer makes it almost impossible to track the owner of objects; shared ownership breaks the single-responsibility principle and, as Sean Parent said, makes the object at the heap a global variable because it is potentially accessible from everywhere.

I can think of only a few justified cases of using shared pointers.

- Shared and weak pointers can be handy for implementing a generic cache mechanism, where the producer of the cache is not the only owner of cached data.

- Boost Asio is another excellent example because ownership of objects in an asynchronous environment can be pretty complicated. This is probably the reason why most tutorials use shared pointers.

Conclusion

Finally, I want to summarize the general recommendations for using a shared pointer.

- Give preference to objects with automatic storage duration over any pointers

- In case a pointer is needed, go first for the unique pointer

- Bear in mind that the overuse of shared pointers may lead to reference cycles

- Prefer

make_sharedover the constructor to save memory allocations - Pass shared pointer by constant reference unless it is a separate thread

- Check the pointer returned from

weak_ptr::lockbefore using it

Update

I have been honored with an invitation to speak at Core C++ 2022 conference about this topic. You can check out my talk at YouTube:

Credits

Thanks to Sergey Pastukhov and Orian Zinger for help.